Romance is not just about cute moments that boost endorphin levels. It can be calculated with a hint of manipulation, or it can unfold naturally. In storytelling, romance is an indispensable tool, for every narrative carries within it a love story. Even if love seems unromantic, there will be an observer skillfully romanticising it.

Romanticisation is inherent to humans. It’s aggressive in its manifestation, as it knows no bounds. It can romanticise both the darkest acts and the noblest deeds. Take, for example, the rise of the global film industry, spurred by the romanticised portrayal of the lives of filmmakers. In the mid-20th century, everyone wanted to be a movie star or simply work on a film set, to see the reality manipulators live, to deal with them, and to learn the craft, only to return to their hometown and smugly share with friends and relatives the tales of Hollywood glamour. In a sense, in the West, such a life contributed to the formation of the illusion of the "American Dream," while in Europe, filmmakers touched on significant themes, had their individual perspectives on ordinary things, and influenced the Western industry with their approach, thus affirming not just artistic cinema with a bright intellectual background but often with a provocative context.

"Love opens a door to your personal hell." – Robert McKee.

One such example is the unfinished project with the striking title "Inferno" (1964), which tells the story of a husband's jealousy towards his wife, leading to madness with hallucinations. The idea came to Clouzot on a sleepless night during a depression, and his reputation allowed him to gather well-known personalities of the industry around the project. At some point, when some scenes were already shot, the American studio Columbia joined the project, altering the fate of the film. Columbia provided the project with an unlimited budget, opening the door to endless experiments and the search for visual effects capable of conveying the hallucinations of the main character. This unfinished film gave the world of cinema a huge number of revolutionary visual effects for its time, albeit at a cost. The project was agonising, and it had to be halted after Clouzot suffered a heart attack. This film became a symbol of unrequited love for Henri-Georges Clouzot, his personal hell.

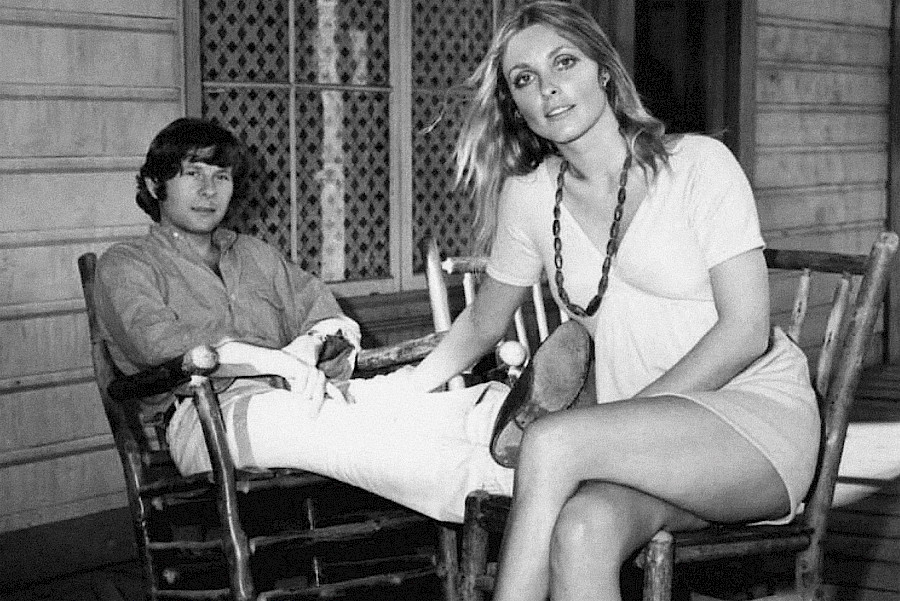

"The few years I had the privilege to spend with her were the happiest years of my life." – Roman Polanski

Roman Polanski's wife, actress Sharon Tate, along with her four friends, was murdered by the "Manson Family" at the behest of the deranged Charles Manson in August 1969 in Los Angeles. During that period, Roman was filming "The Day of the Dolphin" in Europe, but after the tragedy, he stepped away from the director's chair. A year before the tragedy, Roman Polanski adapted Ira Levin's novel "Rosemary's Baby" (1968). Whether this film preceded the real tragedy or simply became an instrument of its materialisation is unknown – yet, the connection is undoubtedly there as what you think about turns into your life. Fifty years after the tragedy, Quentin Tarantino offers his alternative version of the story, where the murderers, in a typical Tarantino style, are neutralised by a stunt double Cliff Booth and Rick Dalton finishing them off. This film can confidently be considered one of Quentin's best in his career, as its tentacles of ideas are quite long and penetrate the minds not only of those familiar with this tragedy but also of those who view cinema as a method of programming reality. For the former, this film protests against the established past that cannot be changed, while for the latter, it creates its own universe in the present, which has the right to exist. When discussing cinematic universes, it would be unfair not to mention the dark DC universe, which, despite recent disappointments, once held promise. Christopher Nolan played a pivotal role in shaping the universe, directing the acclaimed Batman trilogy and producing "Man of Steel." Additionally, he brought Zack Snyder on board, who had previously established the darkness of the "Watchmen" universe four years earlier. While these films have their share of both lovers and haters, it’s undeniable that "The Dark Knight," "Man of Steel," and "Watchmen" are unique in their own right.

"Her characters always fought creatures from another dimension that no one else could see but them. But it was a serious struggle. And Autumn fought such a battle every day." – Zack Snyder

Zack Snyder's "Justice League" is notable for many reasons, but perhaps the most striking aspect is the black-and-white version released in 2011, spanning over 4 hours. The square format, combined with Snyder’s trademark slow-motion sequences, might seem unconventional, but it holds deeper significance. The ability to present something, a rather flexible and all-powerful instrument, yet this instrument has one peculiarity: what is being presented cannot be shown at the moment of presentation; it’s limited to the body of the presenter, and if before the tragedy that happened in the Snyder family, the League was still alive, then after it, it turned into a black-and-white memory of its life before. Zack's daughter, with the symbolic name Autumn, took her own life while her father was working on the film. Naturally, for Zack, there could be no justice. Upon his return, Zack finished some scenes that had not been part of the original script prior to his daughter's passing. These additional scenes served as his frank internal dialogue, offering viewers a glimpse into personal journey. Those who grasped the depth of this dialogue established a profound connection with his seemingly painfully long film, finding emotional resonance in its narrative. Undoubtedly, this rich emotional connection has been idealised by some observers.

Romance is fragile, easily overshadowed by what's deemed "serious." However, what truly qualifies as serious? Consider a wristwatch a symbol of success in society’s structured systems. Yet, genuine happiness resides in the ability to live in the present, free from the need to constantly measure time. Happiness allows for contemplation and embracing the moment. The word "being" holds profound meaning, suggesting that even in deep contemplation, seriousness may not be warranted.